- Article

- Support

- Economic Reports

What is up with the labour market?

For almost half a decade the traditional, internationally recognised methods of collecting labour market data have been unreliable. Therefore, determining the health of labour markets has been at best, an estimate based on an amalgamation of relatively new data series. While the issues in official data since the pandemic are similar across many economies, for ease, we focus on the UK labour market.

A downtrend that the pandemic shone a light on

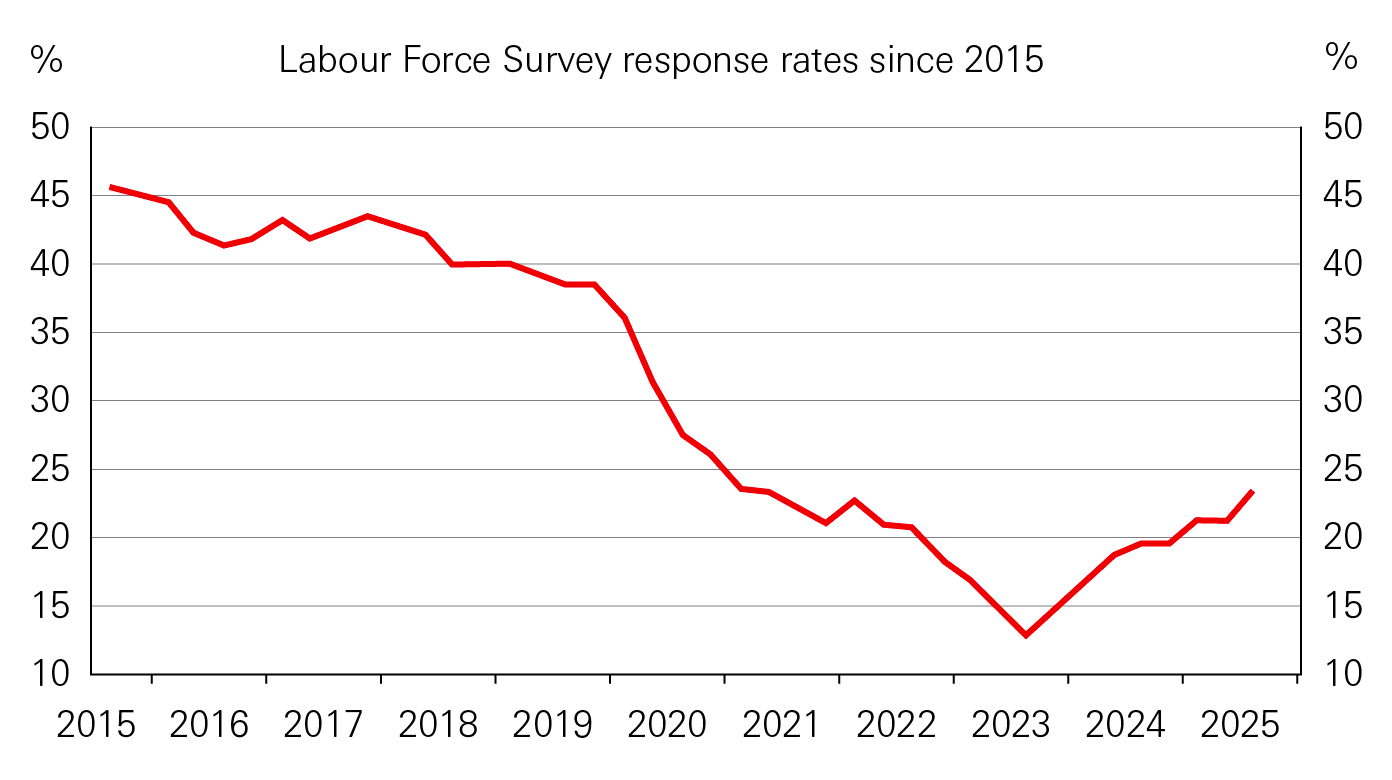

The Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) Labour Force Survey (LFS) has been running since 1973 but has relied on face-to-face interviews; the global pandemic put a stop to that and saw response rates tumble from around 40% to 12%. However, responses were on the decline before 2020, with aging demographics, changes to living arrangements (e.g. rise of rental sector and houses of multiple occupancy), and technology, all wreaking havoc on data collection.

Moreover, a rapid rise in immigration into the UK in recent years has contributed to the need to reweight the survey more frequently as more data on the UK population becomes available. That reweighting, alongside improvements to data collection, including an increase in the sample size, has caused volatility in employment and unemployment data as their impacts are worked through. For instance, the larger sample size took five quarters to be fully reflected in the data.

A new world requires a fresh approach

While reliability has improved over the last year, challenges remain and even the ONS has continued to warn about the results and encouraged users to consider broader data sources, including ‘administered data’ such as from HMRC. However, such data fails to account for many agents in the economy, namely the unemployed that do not claim unemployment support, or those who earn an income (perhaps from self-employment) but do not pay payroll taxes. No data source is perfect, but surveys remain the most reliable and common practise for official statistics.

As it stands, the ONS is in the development stages of a new ‘transformed’ survey. The process began in 2022 but is not expected to replace the current LFS as the official data source until November 2026, at the earliest.

Meanwihle, the transformed survey has continued to also face challenges with response and attrition rates. Many participants simply do not want to participate, in an increasingly online world have attitudes to surveys and sharing information changed? Indeed, a greater focus on online surveys could see demographic challenges with older participants and without incentive, do others have the time or motivation to fill in a survey periodically for over a year. And how will AI play into survey responses.

Perhaps therefore, despite the ONS’s efforts, a broad range of data sources will continue to be needed to assess the health of the labour market. Further ahead, the ONS may be able to utilise AI technology and digital ID cards, if rolled out and adopted widely enough.

Why does unreliable data matter?

In the absence of tried-and-tested, reliable alternatives, these poor-quality statistics continue to be used throughout the economics profession. That matters for several reasons:

- The health of the labour market is a key determinant in the understanding the overall UK economy, where in the business cycle it is, as well as the make-up of businesses and changes to working patterns e.g. rates of participation.

- The LFS underpins other statistics. For example, the level of employment and hours worked are key inputs to calculating how productive labour is and therefore overall productivity growth and potential growth of the UK economy.

- It drives policy:

- For the Bank of England (BoE), the state of the labour market is key in forecasting inflation and therefore setting interest rate policy. As described above, a rise in the rate of unemployment may indicate spare capacity within the economy and downward pressure on inflation. Understanding the labour market is essential for the BoE to be able to understand inflation dynamics.

- For the government, employment and unemployment data drives not only growth statistics but more specifically, projected costings of welfare and potential tax revenues. Such assumptions can have direct consequences for the degree to which the OBR forecasts the government’s fiscal targets will be achieved, and as such the need for policy changes.

Overall, the UK, like other developed nations face challenges in how it collects data, despite there being more data collected in the world today than ever before. Those challenges apply not just to labour market data but to GDP, immigration statistics, and consumer price data, amongst many others. And ultimately, poor data carries potential consequences for households, businesses, and policymakers alike.

Response rates were on a steady decline until the global pandemic accelerated the trend, and have struggled to recover since